Sniping at Carrie Lam is a tempting option for legislators and other politicos these days. It allows the critic to appear independent and outspoken without incurring the risks involved in complaining about the current regime.

It is a bit like flogging a dead horse but perhaps more like pulling the tail of a stuffed tiger; it looks good in your selfies without involving any real danger.

So it came about that there was much wailing and gnashing of teeth over the discovery that Ms Lam’s office, which comes her way on the public tab because one is provided for all former Chief Executives, was costing $9 million a year. Most of this goes on the rent for the office, which is in Pacific Place. Follow-up questions elicited the fact that this arrangement had cost $22 million in two years.

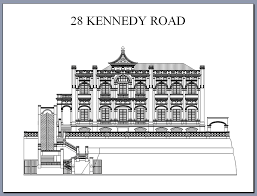

What, cries the well-informed connoisseur of Hong Kong historic architecture, why is Ms Lam not in the building at 28 Kennedy Road, lavishly redecorated and designated for the use of retired chiefs since 2005? Well it’s a long story.

This handsome building is of some age, and is listed as a Grade 1 landmark. It enjoyed a period of modest fame 30 years ago, when it was the Hong Kong home of the Sino-British Joint Liaison Group. The Group was set up under the Sino-British Declaration on Hong Kong’s future in 1985 to settle the finer points of the transition to come, and continued to meet until 1999, two years after the handover.

After this the building seems to have been left empty, as it presented a small problem. It is too big to be a company home, too small to house a government department, and cannot be extensively modified because of its Grade 1 listed status.

In 2005 came a brainwave. Mr Tung Chee-hwa, the first Chief Executive of the Hong Kong SAR, had resigned on grounds of ill health. The former Liaison Office’s home would make a nice office in the mid-levels for Mr Tung and his successor ex-Chief Executives.

As the Legco paper put it at the time, rather prematurely because there was only one Former CE at the time:

The Office provides administrative support to Former Chief Executives to perform promotional, protocol-related, or any other activities in relation to their former official role. The activities include receiving visiting dignitaries and delegations, giving local and overseas media interviews, and taking part in speaking engagements. The office shall provide administrative support for scheduling and making arrangements for public and social appointments, handling correspondence and enquiries, and dealing with general administrative duties.

The paper went on to estimate the annual cost of this arrangement at $2.2 million, most of which would go on the wages of three secretarial staff and a driver.

In 2008 the conversion of the building was completed, marked by the issuing of a triumphant video (link here) and a brief opportunity for members of the public to visit and admire the premises. The first floor has two lounges and a meeting room, and on the next floor up are three offices for ex-CEs. These are quite lavish. You could land an aeroplane on the desk supplied, and there is also a coffee table, armchairs and such. Space has not been skimped.

The provision of three offices seemed reasonable at the time. CEs, it was no doubt supposed, would be appointed at about the age of 60. This was a good guess: age on appointment of the crop so far 59, 60, 57, 60, 64. Average: 60.

Less happily, the planners seem to have assumed that CEs would generally serve the maximum two permitted terms. This would mean the former CE would be on average 70 when retiring. Turning to the relevant Census and Statistics tables we see that a 70-year-old man (CEs are usually men) can on average look forward to another 17 years of life. Under these circumstances – appointment at 60 and ten years in office – when a new CE takes over his predecessor will have 17 years ahead of him, his predecessor in turn will be seven years from the Pearly Gates, and his predecessor in turn will no longer be with us. Three offices will be quite sufficient. On average one will be empty.

Several things went wrong with this prediction. The first is that the expectation of life tables include people who reach 70 already sick and senile. CE candidates are, we hope, picked from the ranks of the fit and frisky. They are likely to be healthier than the aged population in general.

The second problem is the well-established scientific fact that people with prestige do seem to derive some medical advantage from it. Politicians who become ministers live longer, on average, than those who remain mere MPs. Senior civil servants live longer than junior ones, actors who win Oscars last longer than those who do not, and so on. Being at the top of the pecking order is good for your health.

So the provision of three offices may already have been a bit optimistic. What really sabotaged the scheme, though, was the failure of successive Chief Executives to serve a second term. Tung Che-hwa resigned two years and a few months after being elected to a second term. His successor, Donald Tsang, served the remainder of Mr Tung’s second term and was elected to a full term of his own. It was then ruled that he had had the maximum two goes already. The next two CEs both served just one term each.

The current CE, John Lee, will be 69 at the end of his first term, which may appear to him, or to the selectors, to be more than enough. We shall see. But the shortage of desk space for former CEs is probably not going to go away anyway. Leung Chun-ying was the youngest CE so far and Carrie Lam, being female, may well go on for ever.

But there is, at present, no room for Ms Lam in the historic building, leading to the leasing of a substitute in Pacific Place. This can hardly have been the cheapest option.

What is to be done? One legislator suggested that the provision of a free office and associated goodies should be confined to the most recent three CEs, others being presumably left to fend for themselves. This has something to be said for it: do we really want 80plus-year-old dinosaurs meeting visitors, giving media interviews, or making public speeches?

Well I don’t know. People last better than they used to. Speaking as someone who will shortly pass the same landmark I don’t think 80 is that old.

What do they do in other places? There is a problem here. The Chief Executive is not a head of state. In some jurisdictions he would be considered scarcely a Governor. Unsympathetic observers might describe the job as little more than a mayorship.

Diligent searching, however, reveals no examples of places which provide offices for ex-mayors, or even for ex-governors. Google users will be entertained by numerous updates from a Nigerian province where the governor indignantly denies reports that his predecessor has set up an office in the gubernatorial palace.

So, while acknowledging that we are not really comparing like with like here, the arrangement for UK ex-prime ministers is that they can claim up to £120,000 for “office costs and secretarial costs arising from their special position in public life.” As you will see from the table John Major (now 81) is still in business. No claims have been received from Boris (too disorganised?) or Rishi (too rich?) but Liz Truss, famous for her lettuce-length term of office, has already started collecting. So, up to about HK$1.1 million a year.

Much information is available about former US presidents, who are, at least to me, surprisingly numerous. According to the table here in the last 25 years the US has supported eight former presidents of whom five are still with us. This involved a total of 109 ex-president/years for a total of US$125 million, or US$1.1 million per president/year, which would be about HK$8 million in round figures. But this includes the president’s pension, travel and other expenses, which occupies about half of the total, so the figure for office and other amenities would be about HK$4 million.

So by international standards the originally projected figure of $2.2 million a year was generous, the expenditure of $11 million a year on Ms Lam was extravagant. But of course these sums are chicken feed by government spending standards; legislators should have more urgent things to looks at.

I do wonder, though, if former CEs really need a personal secretary and a clerical assistant each. In these digital days we can all type. Are these two people really busy, or are they like the two women standing behind the emperor’s throne in a Chinese opera: not doing anything but an important badge of rank?

I also have some difficulty with the Administration Office’s report that in her two years as an ex-CE Ms Lam has “attended 700 functions”. With all due respect for Ms Lam’s Stakhanovite work ethic, that is almost a function a day. Many of us find that the mention of Ms Lam brings back unhappy memories, some of which were not her fault (COVID) and some of which were. But 350 functions a year? One can only feel terror and pity.